What is an Alexandrite?

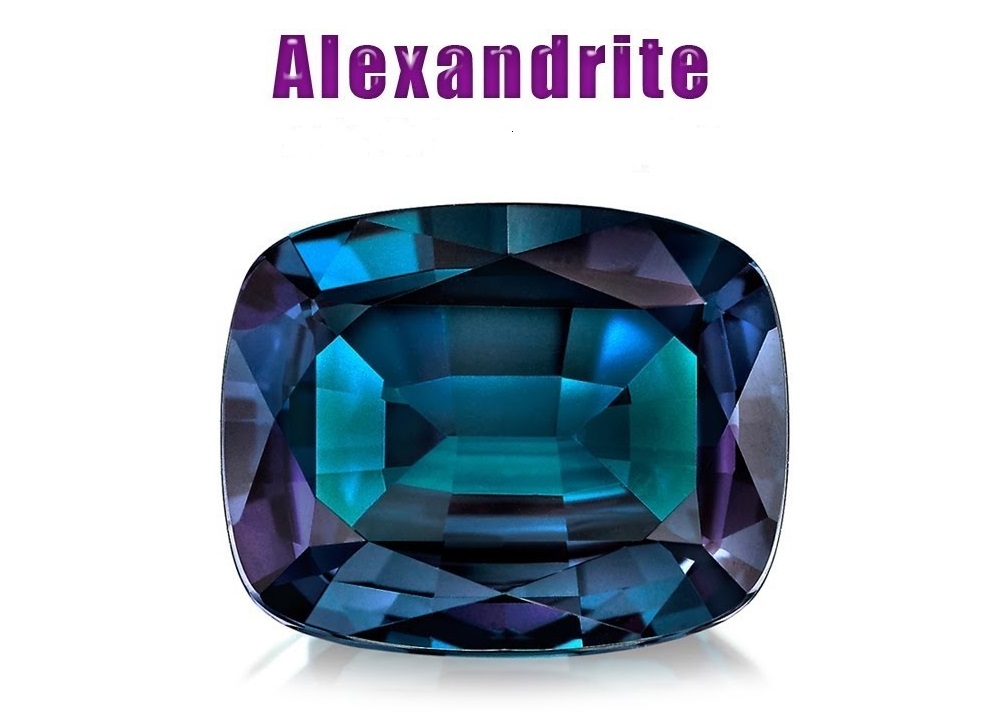

Alexandrite is a color change-variety chrysoberyl and is considered one of the rarest gemstones in the world.

According to GIA, Alexandrite’s finest dual colors are a vivid grass green in daylight and fluorescent light, and an intense raspberry red in incandescent light.

Many modern sources frequently use “emerald by day, ruby by night.” to romanticize Alexandrite’s color.

Alexandrite is the month of June’s Birthstone. Alexandrite is also the 55th Wedding Anniversary Gemstone.

In fact, in terms of rarity, Alexandrite may well outrank nearly all other known gemstones.

While Alexandrites come from many parts of the world, true quality ones share certain characteristics and have been “coveted as one of the rarest and most cherished gemstones of all.” (See AGTA).

Alexandrite Stone (lab definitions)

Gem Photographer Tino Hammid’s depiction of Alexandrite

Ultimately, this determination of what is an Alexandrite is best suited for a lab.

American Gemological Laboratories (AGL): An Alexandrite stone is a Chrysoberyl where the dominant hue distinctly changes under different lighting conditions.

**Color-Shift as opposed to Color-Change: Chrysoberyl (not classified as alexandrite) that displays a more subtle modification to its color under different lighting conditions.

Christian Dunaigre (C.D.): An Alexandrite stone will be a chromium bearing colour-change Chrysoberyl (colour- change: main hue in daylight differs from that seen in incandescent light).

Gemological Institute of America (GIA): Any color change (not shift) makes Chrysoberyl into Alexandrite stone.

GemResearch Swiss Lab (GRS): Alexandrite stone: is a chromium bearing colour-change Chrysoberyl.

Gübelin Gem Lab (GUB): An Alexandrite stone is a variety of gem Chrysoberyl, which changes its main hue from daylight to incandescent light.

The True History Of Alexandrites

The origins of the first Russian Alexandrite (Chrysoberyl with strong change) require official credit to a person named Yakov Vasilevich Kokovin, or Y.A. Kokovin.

According to gem historian Richard A. Wise, Kokovin was the Russian Ural Mountain Mine Manager around the 1800s. (Wise, 2016). Wise’s reference to Kokovin, albeit brief, is to our knowledge, one of the only publications that one person credit for alexandrite’s discovery. Wise’s source for this fact is the book “Russian Alexandrites.” Recently, Kokovin’s contribution was formally acknowledged in an article titled “Gem of the Tsars Alexandrite from the Urals” by the ICA’s InColor Fall 2019 Publication Issue 44. (see Page 24, “It is clear then that Yakov Kokovin should be considered the discoverer of the Ural alexandrites, which was recognized by a number of other researchers.”)

In the book “Russian Alexandrites” by Karl Schmetzer, some of the contributors: George Bosshart, Marina Epelboym, Dr. Lore Kiefert, and Anna-Kathrin Malsy set out to investigate the roots of Alexandrite’s naming in Russia.

The Whitney Alexandrite

This composite image shows how the alexandrite gemstone appears to change color under different light sources: fluorescent on the left and tungsten on the right.The Whitney Alexandrite is a cushion-cut stone originally from the Hematita Mine in Minas Gerais, Brazil. Some of the finest Alexandrite Gemstones come from Brazil.It was gifted to the National Gem Collection by Coralyn Wright Whitney.One of the finest Brazilian Alexandrites, The “Whitney Alexandrite” can be found at the Smithsonian Museum of Natural History.

Weight: 17.08 carats. Estimated Value: Unknown.

Its finest dual colors are a bluish-green in daylight and fluorescent light, and an intense purple, pink, or red in incandescent light.

Color change is the defining characteristic that distinguishes alexandrite from other chrysoberyl varieties.

While other minerals—can display color change, few show such vivid saturated color change as fine alexandrite.

For this reason, the color-change phenomenon itself is called “the alexandrite effect.”

Today, most, if not all, Alexandrites you might see in jewelry do not come from Russia.

We occasionally have some Russian Alexandrites from sale. One of the ones we currently have can be seen here.

A lot of Alexandrite research continues to use the following descriptions: “Emerald by day, Amethsyt by night” or even “Emerald by day, Ruby by night.”

However, contrary to this cliché, the reality is that such dramatic color shift is the rarest type you can find.

Although we often see references to Alexandrite changing from a green to red, in reality this type of color change in Alexandrite is so rare as to be non-existent.

Russia’s Controversial Alexandrite History

After combing through the book for Kokovin’s name, it appeared that documents supported the idea that Kokovin’s contributions to Russia during his life were large. (Schmetzer K. , 2010). However, controversy surrounded the recorded history of what happened to him. Some research suggests that he misjudged high value emeralds he oversaw. (Schmetzer K. , 2010). Again, it is unclear whether this was true or not. The reason for Kokovin being relieved of his duties is still speculated.

Kokivin was even imprisoned. In fact, “his health was poor as a consequence of losing his position and all the honor bestowed on him for his work as a lapidary artist and stone cutter…” Id. Kokovin’s downfall took place with the knowledge of Alexander’s father, Tsar Nicholas Id. Moreover, Kokovin shared a well-documented animosity with another central character behind Alexandrite’s first recorded discovery: Count L.A. Perovskii.

The Discovery of The First Russian Alexandrite

The earliest documented connection to the discovery of alexandrite in Russia came from the Russian Imperial Mineralogical Society (Established in 1817). (Schmetzer, 2010).

The discovery of the first Russian Alexandrite itself has divergent origins. This is even clear from GIA’s own characterization of Alexandrite’s origin: “discovered in 1830 by miners in the Ural Mountains of Russia…” (GIA, 2018) (Emphasis Added). The fact that an institution like GIA simply uses “miners” to credit discovery further shows the ambiguity behind crediting someone for the new variety designation.

Besides the difficulty in narrowing the exact individual who mined it, an alexandrite’s chameleon type attribute would further complicate realizing its true identity. This complication is due to the fact that Chrysoberyl (the mineral Alexandrite falls under) had been already discovered prior to 1830. Therefore, in order to distinguish chrysoberyl from beryl or emerald, a second person (besides the actual miner) would have to have some mineral knowledge. It appears that after identifying it as chrysoberyl, and seeing that the chrysoberyl underwent color change, the questions arises as to who had the eureka moment of coining the new varietal name.

Given these nuanced circumstances, you can imagine crediting a single individual as responsible for discovering the first alexandrite in Russia to be tricky. On the one hand, one could say that finding the mineral itself would mean credit for discovery. On the other hand, some might say that taking the steps to determine that it was simply chrysoberyl with prominant color would warrant credit.

Where did the name “Alexandrite”come from?

By many accounts and published sources, Finnish mineralogist, Nils Gustaf Nordenskjold, is credited with finding the first samples of Alexandrite material in Russian emerald mines. (AGL, 2008). Consistent online and physical resources further suggest that Nordenskiöld (sometimes spelled Nordenskjold) came up with the suggestion of the actual name variation “Alexandrite.” Currently, this remains to be the most consistent story: that the name Alexandrite was Nordenskjold’s idea. The story stems from Nordenskiöld

coining the name Alexandrite after being inspired by the future tsar Alexander’s birthday celebration in the Ural Mountains area where the stone was found.

Over the course of the book “Russian Alexandrites”, the Nordenskjold’s family archive is reviewed along with correspondence written by him. In the book they report that, prior to 1842, the researchers say they were unable to find the word “Alexandrite” in letters written by Nordenskjold. In fact, there is some suspicion surrounding the Russian authorities at the time being involved with censorship. (Schmetzer K. , 2010) You can imagine the dramatic control the government had over the country given the future demise of Tsar Alexander. More on Russian Alexandrites…

Alexandrite Auction History

Brazilian Alexandrite 9.99 carats sold by Christie’s Auction House

One of the most expensive Alexandrites from Sri Lanka was sold for at the Magnificent Jewels New York Auction for $557,000.00.

At 18.23 carats, the price would be just over $30,000 per carat.

The stone included a supplemental letter from the American Gemological Laboratories attesting to the rarity and prestige of the alexandrite.

Brazilian Alexandrite 19.05 carats sold by Christie’s Auction House

Notable Alexandrites Sold at Christie’s Auction House

Over the years, some of the largest known Alexandrites have been sold at the Christie’s Auction.

Here are some of the most notable ones:

One of the largest Alexandrites from Brazil sold over 10 years ago.

In October 2007, Magnificent Jewels Auction New York, at a whopping 19.05 carats, The Alexandrite and Diamond Ring sold for $959,400.

That comes out to over $50K Per Carat!

Brazilian Alexandrite 15.58 carats sold by Christie’s Auction House

4 years later, a slightly smaller Alexandrite from Brazil would fetch an even higher price.

In the Hong Kong Magnificent Jewels Auction, an Alexandrite and Diamond Ring weighing 15.58 carats sold for 7,220,000 HKD, the equivalent of $931,000 or just under $60,000 per carat!

In 2017, at 9.99 carats, another Alexandrite from Brazil sold for $313,000.00

The Alexandrite Effect

Alexandrite Origins

Origins are best left for an independent lab to determine. Additionally, it has been known that imitation alexandrites have been sold over the last 100 years. These synthetic or lab created alexandrites can be difficult to distinguish without proper equipment.

Our experience has led us to conclude that color alone can be extremely helpful in ruling out origins.

On the one hand, certain colors can be indicative of where an Alexandrite comes from.

On the other hand, certain colors are good evidence of where it is not from.

For example, a brown color modifier will rule out Brazil as an origin.

Again, this is our opinion only.

Alexandrites from Madagascar

Many sources assume that gemstones from the African Continent will always generally have a darker or browner tone.

This presumption ignores the fact that some of the finest Alexandrites produced in the market today have come from Madagascar, and can have a Blue-Green Color under daylight.

Lower quality Alexandrites from Madagascar can have brown dominant colors.

Typically, muddy green color often seen under daylight, will almost always have a brown modifier under incandescent light.

The best quality Alexandrites from Madagascar will always appear green dominant.

The purity of the green is preferably modified with a bluish tone.

The purple will also have pink-purple intensity that rivals top quality Alexandrites from other regions. Here are some of our GIA certified Alexandrites.

Alexandrites from India

Indian Alexandrites are know for a distinct pure green dominant daylight appearance.

Some of our gemstone mining connections in India have informed us that most Indian Alexandrites coming from the Orissa mine, come in smaller melee sizes ( < 0.5 cts.).

The daylight color usually appears in a richer grassy green hue. The incandescent color is typically not as dramatic in its purple.

In fact, the purple intensity can be described as medium to light in saturation.

Notwithstanding the limited production, an occasional blue-green to rich purple Alexandrite from India will surface.

Alexandrites from Sri Lanka (Ceylon)

Commonly referred to as the “Island of Gems” it is no surprise that the famous exotic country produces Alexandrites.

Alexandrites from Sri Lanka tend to have yellowish-green appearance in daylight.

Ceylon Alexandrites are also usually larger than Alexandrites found in other countries.

Although larger, they won’t typically have strong color change.

The few larger size Alexandrites with strong color change from Sri Lanka remain extraordinarily scarce.

Our experience over time has shown us that distinguishing Madagascar and Ceylon Alexandrites is very difficult.

The reality is that local suppliers source rough alexandrite from Madagascar and cut the material in Sri Lanka.

Christie’s Alexandrite (Ceylon Origin) 29.41 cts

Once polished, suppliers may lose track of a material’s actual source.

This leaves labs in the best position to determine the origin by making the distinction between Madagascar and Ceylon.

Yellowish-Green Alexandrites from Sri Lanka will often have the same lighter hue modifier under incandescent light.

Alexandrites from Russia

The most prized origin of Alexandrite.

Russian Alexandrites are known to come from the Ural mountains.

Finding gem quality Alexandrite over 1 carat from Russia today is extraordinarily difficult.

The rough that comes from Russia is usually Emerald, and any presence of Alexandrite is usually poor quality.

Many commentaries refer to Alexandrite as “Emerald by day, Ruby by night,” are likely to be referring to Russian Alexandrites that show such dramatic color change.

Russian Alexandrites with blue-green colors can be confused with any source.

Old cutting, or faceting may lend credit to origin identification.

An absence of inclusions will also make it difficult for identifying Russian material.

We suggest relying on two lab reports to confirm any Alexandrite with Russian Origin.

Alexandrites from Tanzania

Tanzanian Alexandrites remain elusive.

Labs have difficulties classifying this origin due to its strikingly similar characteristics of both Brazil and Madagascar.

Alexandrites from Tanzania in our experience usually display a lighter Mediterranean Bluish-Green color under daylight.

Under incandescent light, the Tanzanian Alexandrites that we have seen nearly always show a dramatic color change.

An Alexandrite from Tanzania

During one of our most recent trips to the country, sources dismissed the notion of finding more Alexandrites in any local mines. Most Alexandrites from Tanzania came from Lake Manyara in the north and Tunduru in the south. (Source GIA).

Alexandrites from Brazil

In the early 1980’s, a significant mine of Alexandrite deposits was discovered in Brazil.

Commonly referred to as the “Hematita” mine, the discovery immediately led to an influx of independent miners to the area. Other areas include Bahia and Espírito Santo, but are of lower quality Alexandrites.

One can say this was the “Gold Rush” of Alexandrites that quickly dwindled out after 12 weeks of digging (Source: Richard W. Wise, Secrets of The Gemstone Trade, 2016).

Top quality Brazilian Alexandrites appears rich bluish-green under daylight, and transforms into an intense purple in incandescent light.

Alexandrite from Brazil

Although labs will never rely on appearance alone to classify this origin, once you see a Brazilian Alexandrite, its specific color becomes a unique hue in your color palette. This is what it looks like.

Since the discovery of the deposit, production of over 1 Carat Quality Size Alexandrites has been nearly extinct.

Those in the trade know that a gemstone’s desire is sometimes inextricably tied to its origin.

Blue Sapphires have Kashmir.

Rubies have Burma.

And Paraiba Tourmalines have Brazil.

One could argue that for Alexandrites this would be Russia, but the truth is that the current most exceptional looking Alexandrites are from Brazil.

From a strictly color-change point of view, you be the judge of whether the Russian Alexandrite or Brazilian Alexandrite is more impressive.

Unlike its “green to red” folktale Russian counterpart, the Brazilian Alexandrite displays an awesome bluish-green color under white light, and magically changes to a deep rich purple under incandescent light.

The Brazilian Alexandrite has yet to be fully appreciated by the gem world.

This is probably due to its exorbitant price.

Good-quality, carat-size Alexandrites from Brazil can exceed Diamond carat-size equivalents.

The current major Alexandrite sources include: Sri Lanka, Madagascar, Tanzania, Brazil, Zimbabwe, Mozambique and India.

However, it appears that quality Alexandrite is becoming more and more difficult to find everywhere.

Additionally, like the Russian Alexandrite, the Brazilian Alexandrite has already steadily declined in quality production.

While origin can seem important in buying an Alexandrite, labs will likely charge extra for this determination.

It may be worth the additional fee for someone claiming an Alexandrite is from Brazil, or Russia.

However, a reputable lab report is essential for truly identifying the stone as natural without any treatments.

Classifying Alexandrites

The original reference to qualify an Alexandrite, as a Chrysoberyl that changes from green to red, is far too restrictive.

“A more apt description would indicate something like ‘greenish’ in fluorescent light and ‘reddish’ under incandescent light,” says Christopher Smith of American Gemological Laboratories (AGL).

“Even though the full range of colors possible is more expansive than that.”

Christian Dunaigre, who currently manages his own gem laboratory in Thailand as well as one of the only on-site mobile gem testing services, also believes finding an Alexandrite with a “pure ruby red” color is nearly impossible.

Moreover, Mr. Dunaigre thinks most Alexandrites have modifiers and seldom have pure changes that are limited to one hue.

Although anecdotal, you can probably go to any gem trade show and ask to see an Alexandrite lab report (commonly referred to as a “certificate”) of any type and discover this yourself.

Gem identification reports almost never limit themselves to just one color when describing the color shift under white (daylight) light and incandescent light (lamp yellow light).

Common examples include:

Bluish Green to Purple,

Green to Greyish-Purple,

Green Blue to Purplish Red,

Yellowish-Green to Brownish Purple,

Green to Purplish Pink,

and many other 2 to 1 and 1 to 2 type color changes.

My doubts about finding a purely red Alexandrite were even further solidified by Gübelin’s own Dr. Anna Malsy.

Dr. Malsy has written extensively about colored gemstones, and has published a thorough article discussing how to identify the difference between synthetic Alexandrites and genuine Alexandrites.

She described seeing “purple, reddish-purple or purplish-red” Alexandrites, but hardly ever seeing purely red ones.

Like Diamonds, there are additional C’s that can be used in guiding yourself to Alexandrite.

Besides Clarity, Carat, and Cut, you also have color Change (instead of just color) and Classification (Lab Classification).

Ideal Lighting Conditions to See Alexandrite’s Color Change

The best way to look at an Alexandrite is under two different lighting conditions:

1. White/daylight to see the first color (ideally green with a blue/ brown/yellow modifier).

The Lab Manual Harmonisation Committee (LMHC) suggests the daylight corresponding to a range between “5500K to 6500K.”

2. Yellow/warm light to see the second color change (red, purple, pink with various possible modifiers such as brown, yellow, orange).

LMHC suggest comparison of incandescent light corresponding to a range between “2700K and 3600K.

Alexandrite or Chrysoberyl?

This Alexandrite shows weak color change, and may be called just Chrysoberyl by some labs

Labs are in the best position to make this determination. Gem labs have the right equipment to distinguish between chrysoberyl, alexandrite, and lab created alexandrite. It is always in your best interest to use a gem lab to identify rare gemstones like alexandrite.

What Makes A Stone Rare?

We believe that every gemstone’s degree of rarity depends on two critically connected elements: Availability & Market Desirability. At all times, this concept of market desirability must be considered through a lens of an informed collector.

For example, an informed collector knows:

- Marketing can influence a person to want anything.

- Jewelry that is beautiful and fashionable does not translate into true value.

- Just because a gemstone is very limited in availability, does not mean it will be desirable if it looks ugly.

Availability defined:

The degree in which a gemstone can be readily obtained.

Market Desirability defined:

The characteristics that a gemstone possess that are desired by an informed collector.

The rare characteristics include:

- Treatment. Is the stone Untreated or Treated. Simply put: did it come from the earth naturally or was it enhanced through a foreign process? Being Natural →Most important factor = More Rare

- Size. The bigger it is, the more difficult it is to find. Carat Weight ⇑ = More Rare

- Origin. Exotic parts of the world are known for specific gemstones and fetch more $ = More Rare

- Clarity. Stones without any eye visible inclusions will be worth more than ones that have blemishes and interior obscurities. Clean looking gems = More Rare

- Cutting. The stone’s superficial brilliance and shine= Stones are sometimes cut in a way that maximizes light reflection= More Rare

- Shape. Smallest factor in rarity, still- odd or fancy shapes can give an additional layer of uniqueness making it= More Rare

The Most Rare Stones will always have:

Low Availability + High market desirability

Examples of how Availability and Market Desirability interact

Example 1:

A round shape white diamond, 1.05 ct., with an F color grade ,an SI2 clarity grade, and a Triple Excellent Cut, white diamond is highly desirable in the market (high market desirability).

However, finding another round diamond with similar characteristics is easy.

Additionally, the origin of where it came from is likely untraceable.

This would make it even easier to be replaced

. Therefore, a white diamond has high availability + high market desirability.

Example 2:

An oval shape Tanzanite gemstone, over 3 carats, with intense purple color, and no eye visible inclusions, has market desirability because of its exotic origin (only found in Tanzania).

All these rare characteristics might make a novice collector assume it is very rare.

However, while Tanzanites are sought after, there is an abundance of availability, moving it towards the bottom of the Rarity Pyramid.

Therefore, tanzanite also has high availability + high market desirability .

Obviously, economic forces will always be an X factor on market desirability.

We believe educated collectors will have to use their own judgment to determine which of the rare characteristics is the most important when deciding on beginning a collection.

6 Characteristics of A Rare Gem

1.Untreated v. Treated

Once you have a reliable lab report, you now have a better road map to do research online.

With the proper lab report in hand, you should now analyze each element.

We suggest focusing on treatment after the gemstone has been identified.

Treatments will often include a notation paragraph on whether it is synthetic or lab created under the treatment heading of the report.

Sometimes the paragraph will be towards the bottom, so be cautious not to miss it!

Additionally, the American Gem Trade Association (AGTA) is a wonderful place to look up any treatment.

The AGTA’ standard for treatment disclosure was even adopted by the International Colored Gemstone Association (ICA).

| Bottom Line: The most rare gemstones will always be ones that are “natural.” (free from any enhancements). |

2. Carat Weight (SIZE)

In the world of rarity, size is crucial.

The average person who may not know anything about gemstones will no doubt understand that a bigger gemstone is more valuable.

As sizes move from 0.99 cts. to 1 ct, prices will change substantially.

While each gemstone varies, consideration must be given for differences between 2 to 3 carats. 4 to 5 carats, and moving upwards.

You will often see 20 Carat + sizes in museums.

| Bottom Line: The more a gemstone weighs, the more rare it will be. |

3. Origin

Origin is probably the least known element of rarity.

Two gemstones that share identical attributes of size, weight, shape and appearance can potentially have two completely different values based on what country they came from.

Part of the reason for the difference in value comes from the scarcity associated with certain territories.

For example, although rubies are often seen in the market, a ruby from Burma is highly prized.

This is because Burma is considered a unique type of origin for this particular gemstone.

Today, many people might not realize that a family ring might come from an exotic country that is desired by collectors.

Some gemstones will not be affected by their origin at all.

One of the biggest differences between a gemstone and a diamond is the ability to trace where they come from.

Diamonds fall short of this unique quality.

Within the trade, dealers will often use origin as a way to convey an additional layer of value.

More often than not, particular origins will only be accepted by certain laboratories with the highest reputation for accuracy.

| Bottom Line: Origin is only important for certain gemstones. However, for those gemstones that it is important, the effect on rarity can be exponential. |

4. Clarity

For what they lack in origin, diamonds have been useful in contributing to the understanding of clarity.

While colored stones usually put little emphasis on what the precise clarity of a gemstone is, it is still worth knowing the differences between “IF” (internally flawless) and “I1” levels of clarity.

According to GIA, there are 11 clarity grades: Flawless (F), Internally Flawless (IF), two categories of Very, Very Slightly Included (VVSI or VVS2), two categories of Slightly Included (SI1 or SI2), and three categories of Included (I1, I2, or I3).

For the purposes of colored stones, its easier to describe the stone as either: loupe clean (that is, under the loupe- no inclusions are visible), eye clean (under the loupe some inclusions are visible, but are difficult to see with the naked eye), & included (this usually means the stone has visible inclusions that can be seen with your eyes).

The presence of inclusions adds character to a gemstone.

It is only when these inclusions rise to a level of detracting attention away from the gem’s beauty that it becomes an issue to be avoided.

| Bottom Line: Loupe clean and eye clean gemstones will always be dramatically more rare than ones that are visibly included. |

5. Cutting

The cutting of a gemstone dramatically effects how the gemstone appears. When a gemstone first makes its way from mine to market, a lot of emphasis is placed on maximizing the carat weight.

The person who makes the initial investment in rough (uncut gemstone material) will always make more money when the stone weighs more.

A stone that weighs more will fetch a higher per carat price. As a result of this, some gemstones might have their beauty slightly compromised.

The most valuable and rare gemstones are cut in a way that maximizes both weight, and luster.

Luster comes from well proportioned gem. Light is better able to reflect throughout the gemstone and appear brilliant.

A poorly cut gemstone might allow light to fall through the middle.

This description, usually described as a “window” gives a transparent look that is typically may or may not be attractive to some people.

Another type of poor cutting is what the trade calls “heaviness.”

A stone that is “heavy” has a longer bottom.

The heavy stone is cut in a way that prevents it from looking proportional.

This might also happen because the cutter may look at a piece of rough and determine that the color is concentrated at at certain area of the stone.

In this scenario, cutting the gemstone proportionally might have an adverse effect of diluting or even worse, removing the color altogether.

Cutting can also alter whether the stone’s weight is presented in the most efficient way.

For example, a 5 carat stone with a very heavy bottom, may look like it is only 3 carats in size because the diameter is the same as well proportioned 3 carat stone with great cutting.

In this example, the “face” of the stone is small.

This is opposite of what some may call “spready,” which is another way of saying that the stone looks much bigger than it actually is.

The opposite example of above, where a 2 carat stone is cut in a way that it looks like its 3 carats when mounted in jewelry.

Again, bad cutting can cause the face of the stone to look much smaller than the actual weight it has.

| Bottom Line: Rarity will go up when the stone is cut in away that maximizes shine, distributes weight evenly. |

6. Shape

The shape of the stone has the least effect on the rarity.

However, certain shapes have historically been less desirable.

Pear Shapes, Marquis and Round might be popular shapes for smaller sizes.

However, gemstones over 5 Carats are not commonly cut in these shapes.

This is due to the low demand for fancy shapes.

Ovals, Cushions, & Emerald Cuts are more desirable when it comes to large sizes.